A Tree Older than Austin

on the live oak around the corner

For a handful of years, my office was on Austin’s East 11th Street, above the Texas Music Museum and across the street from Franklin Barbecue, where the lines for their famous brisket started forming at 9am. I could see people waiting for their plates of meat from the window beside my desk.

Some days I would walk to work and home, though I wouldn’t call the office walking distance from my house. The route led me down the hill and out of my neighborhood, across the river on the I-35 bridge, and up East Austin past an elementary school, a few churches, and a scrap metal yard. It took about 45 minutes each way.

It's the walk home I want to tell you about.

Walking a straight shot south on Waller Street, the land disappears into the river, then rises again on our little hill. You can find the hill because of the trees, and particularly because of one tree, a live oak which stands so tall and grand that I could see it from miles away. It felt like a map home.

**

The house behind the tree has been empty for more than a decade, despite the endless development in our neighborhood. Years ago, the owner of a commercial property adjacent to the house purchased it from the single guy who’d lived there, offering him enough money to buy a new house in the more upscale neighborhood across the highway. The backyard of the house has a stunning view over the city, but the owner has left everything to sit and rot. The back deck has disintegrated, windows have been broken, and the garage has been boarded up with plywood.

Recently my husband and I took a tape measure and walked around the corner. We waded through the high grass to measure the circumference of the tree’s trunk. I placed my hand on its knobby bark, looked high into its branches, then found a spot 4 ½ feet from the ground, as the internet told me to, before stretching out the tape. The tree measures almost 15 feet around. According to Google, that makes it somewhere close to 222 years old.

It began as an acorn around 1803.

**

The tree around the corner is neither the oldest tree in Austin nor a landmark, tucked at the end of a cul-de-sac in the “pocket neighborhood” I call home. It may be one of many trees its age in the city, but it’s the one I know best.

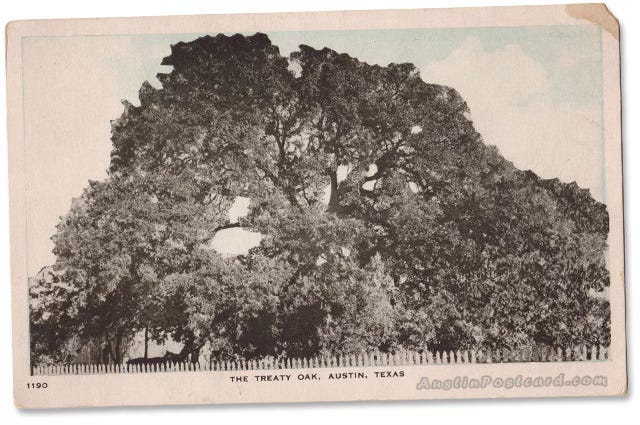

The most famous live oak in Austin is the Treaty Oak, a tree that still stands, or at least partially stands, over in central Austin, not far from the flagship Whole Foods store. It’s estimated to be 500 years old, and one of a group of legendary Council Oaks. Though there is little evidence proving their existence, the Council Oaks were said to be trees where Comanches and Tonkawas held conferences, made pacts, and celebrated ceremonies. The last of these trees, the Treaty Oak, is supposed to be where Texas founder Stephen F. Austin signed a boundary agreement with Native Americans in the 1830s. That historians have argued this unlikely has done little to dampen the tree’s fame.

Apart from the tree’s mythology, one thing is certain: In 1989 a guy tried to murder it. He drew a “magic circle” of Velpar, a herbicide, around the Treaty Oak, pouring out enough poison to kill 100 trees. First the grass turned, then the leaves started to change, then a soil sample revealed the truth. And then the story went around the world.

Articles appeared in the New York Times, National Geographic, Sports Illustrated. People sent get well cards, placed bowls of chicken soup around the tree’s base, held vigils. A team of 22 experts from across the country gathered to work on the tree, and Texan Ross Perot offered a blank check to cover the expense of saving it. And somehow this tree that had already witnessed centuries of history survived. It came back at 1/3 of its size and dropped its first set of acorns eight years later.

The perpetrator, a “love-sick occultist” trying to cast a spell, spent three years in prison.

**

In 1803, there weren’t yet European colonists in what we now know as Austin. Spanish friars had arrived in the 1700s, but they soon abandoned the area and headed south to what became San Antonio, establishing several missions, including the Alamo, near the banks of the river.

In 1803, Stephen F. Austin was 10 years old and living in Missouri. Sam Houston was also 10 years old, a boy growing up on the Timber Ridge plantation in Virginia. Future Republic of Texas president Mirabeau Lamar was a five-year-old in Georgia.

In 1803, this area was home to nomadic tribes, the Tonkawa moving in where the Comanche and Lipan-Apache once roamed. Barton Springs was a watering hole around which Native Americans rested, drank, and cooked. The Blackland Prairie to the east of town still held herds of buffalo.

In 1803, the University of Texas, its bell tower now visible from the street in front of the tree, was 80 years from being established.

**

There are parts of the country where a 200-year-old tree is no big deal. I often marvel at the towering trees behind my in-laws’ house in Connecticut. California has redwoods you can drive through, and the firs and hemlocks of Washington’s old growth forests inspire awe.

But this is the tree that has stood through the centuries of our little hill, that knew the city before it became a city, the neighborhood before it was a neighborhood. It is a place where you can see “the past coming through,” as Marla Akin put it when talking about the Austin of old.

**

Months ago, a billboard was erected on the street in front of the tree, announcing the demolition of the old house. I took a picture when I saw the sign, less because of the news about the house and more because of the brash machismo of the billboard itself. A gray wrecking ball sails in front of a Texas flag. And a tagline reads: when we knock em down they stay down. The English teacher in me wants to argue with this sign for both its lack of punctuation and the fallacy of its argument. Do demolished houses rise again under the cloak of darkness?

As of this writing, the house still stands. Weeds have grown so high in front of the demolition billboard that its tagline is no longer visible. Eventually, though, the house will come down, the property developed into something new. The tree should be protected through Austin’s heritage tree ordinance, but who knows anymore? In 2017, Texas Governor Greg Abbott, who is still in office today and plans to run for a fourth term next year, signed a bill undermining local tree ordinances across the state. He called the protection of trees on private property an overreach and “socialistic.”

If I allow myself to, I worry for that tree.

When we moved to our house, the property next door had several well-established oak trees—trees not as old as the one around the corner, but still powerful and lovely. After the construction of the two duplexes on the property, projects that protected the trees but changed the environment around them, one oak and then another came down. The first fell across the driveway to the rear duplex. The next landed right on the owner’s cars.

**

Austin’s trees have always been in a dance with Austin’s development. If the Treaty Oak was the final of the legendary Council Oaks, that’s because all the others had been cut down to make room for houses. In fact, in the 1920s, the owner of the property where the Treaty Oak stood, Mrs. W.H. Caldwell, groused about how the tree was preventing her from developing the property. Its canopy reached 127 feet, taking over the land around it in ways that were both glorious and inconvenient. Ultimately, unable to afford her taxes on the undeveloped land, the widow sold it to the City of Austin for $1000.

The live oak around the corner has lived through the establishment of Austin and the State of Texas, through the forced relocation of indigenous peoples and the building of roads, houses, and eventually the highway. It has stood as the city has gone from small outpost to high tech center, the glint off the shiny downtown buildings just about making it to its canopy. It has been shade-giver, squirrel-feeder, sentinel. It has been my map home. But will it withstand the changes to come?

Programming note: My Write Together Saturday workshops return in September and continue through the fall. For more information on those and upcoming offerings, or to join the waiting list for my Artist Way workshops, see my website.

Vivé, You are such a close observer and thinker, this essay is brilliant. many thanks !

...Thank you Vive for your telling of this fascinating tale. I, too, have become enamored by the presence of the grand trees that populate my areas where I both live and explore. Having read a couple of years ago, some library books on both ancient trees and old growth forests, my eyes have been opened to noticing them everywhere I wander. The only title that I can recall is "The Secret Life Of Trees", which expounds on how trees communicate and aid in survival of their homes. And lastly, I want to point out to my "Cavello Cousins" that I also learned in my readings that the area in the Norheast that has most ancient of standing tress is in Pelham Bay Park, The Bronx USA !!!